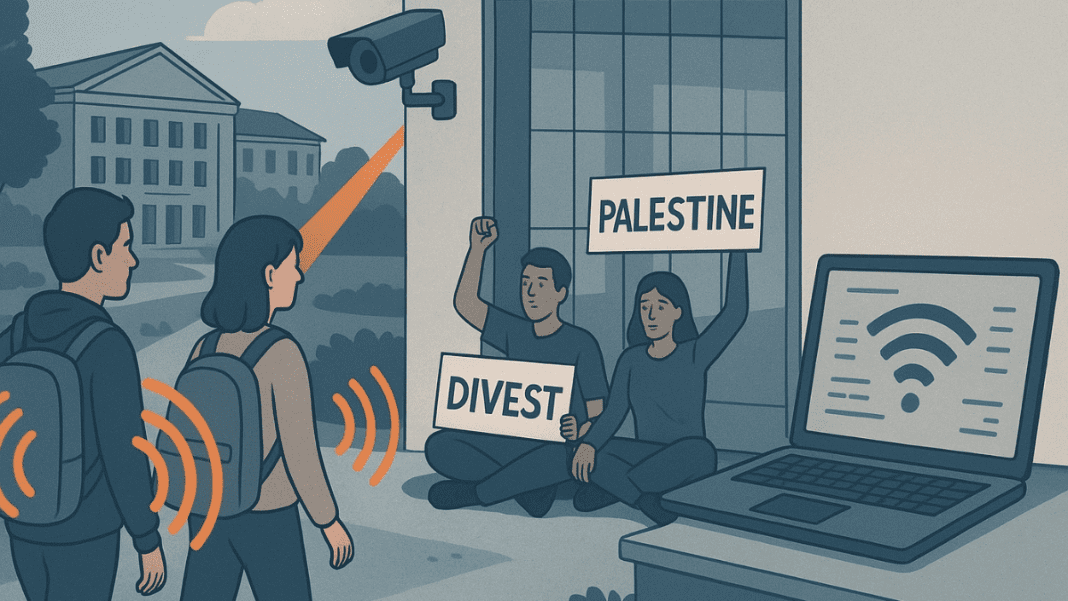

The University of Melbourne broke privacy laws in 2024. It used Wi-Fi tracking to monitor students and staff during a large protest. The Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner (OVIC) called it a serious breach. The watchdog said the action went against human rights principles.

Privacy Watchdog Flags Breach

The university tracked devices connected to its Wi-Fi network to identify people who took part in a sit-in protest calling for the institution to cut ties with weapons companies. The protest lasted ten days, disrupted hundreds of classes, and affected thousands of students.

Investigators said the university did not only use Wi-Fi data. It also used CCTV footage, student card photos, and staff emails. Officials used this information to make a list of suspected protesters. They approved this use of data in just one day. In the end, officials identified 22 students and 10 staff. Most of them got formal cautions. Others faced disciplinary action.

Official records said the university did not suspend or expel any students or staff. But activist groups claimed otherwise. They said the university expelled at least two students and suspended two more during the OVIC investigation. They also said the university used Wi-Fi location data as evidence in these cases.

Continued Tracking Raises Alarms

The controversy did not end with the first protest. In late 2024, activists again accused the university of using Wi-Fi tracking. They said the university used it to find students in another sit-in. This sit-in took place inside an academic office. The protesters opposed research linked to overseas institutions.

Some of the students involved said they even received emails containing CCTV images of themselves inside the building. However, OVIC did not flag this as a breach under existing laws.

The commissioner said the university never clearly told students and staff that it could use their Wi-Fi data for misconduct cases. The report said the university failed to get consent. It also changed the original purpose of collecting the data without telling the community.

Cyberattack Catastrophe: How Hackers Can Endanger Human Lives ?

The university introduced the Wi-Fi system in 2016 to monitor building use, improve services, and help with event planning. At the time, privacy experts received assurances that the system would not track individuals.

The commissioner described the case as an example of “function creep,” where technology set up for one reason is slowly used for another without proper notice or permission.

In April 2025, the university changed its Wi-Fi terms of use while the investigation was still happening. The new rules said all users must agree to Wi-Fi tracking. The tracking could be used to detect unlawful or antisocial behavior and breaches of university policy. These changes let the university keep using Wi-Fi location tracking, even as criticism grew.

Reaction From Students and Rights Groups

The move has caused strong backlash. Human rights groups said that the university’s surveillance of students has created a climate of fear. They warned that the new Wi-Fi terms and protest rules could have a “chilling effect” on free expression and student life.

Staff unions also condemned the university, accusing it of acting like “Big Brother” and destroying trust on campus. Protest organizers advised students to turn off their Wi-Fi and use VPNs to avoid being tracked in the future.

Insider revenge cyberattack freezes 1,000 workers — Eaton hit with massive disruption and losses

Activists said the university had misled the public by previously claiming it could not identify individuals through Wi-Fi data. They called this statement a “lie” and pointed out that disciplinary notices and misconduct investigations were clearly based on digital tracking.

The OVIC report confirmed that the university broke privacy rules by not asking for consent. But the university had already updated its Wi-Fi terms of use. Because of this, officials did not issue a compliance notice. They accepted the new rules as an improvement, even though it meant surveillance could continue.