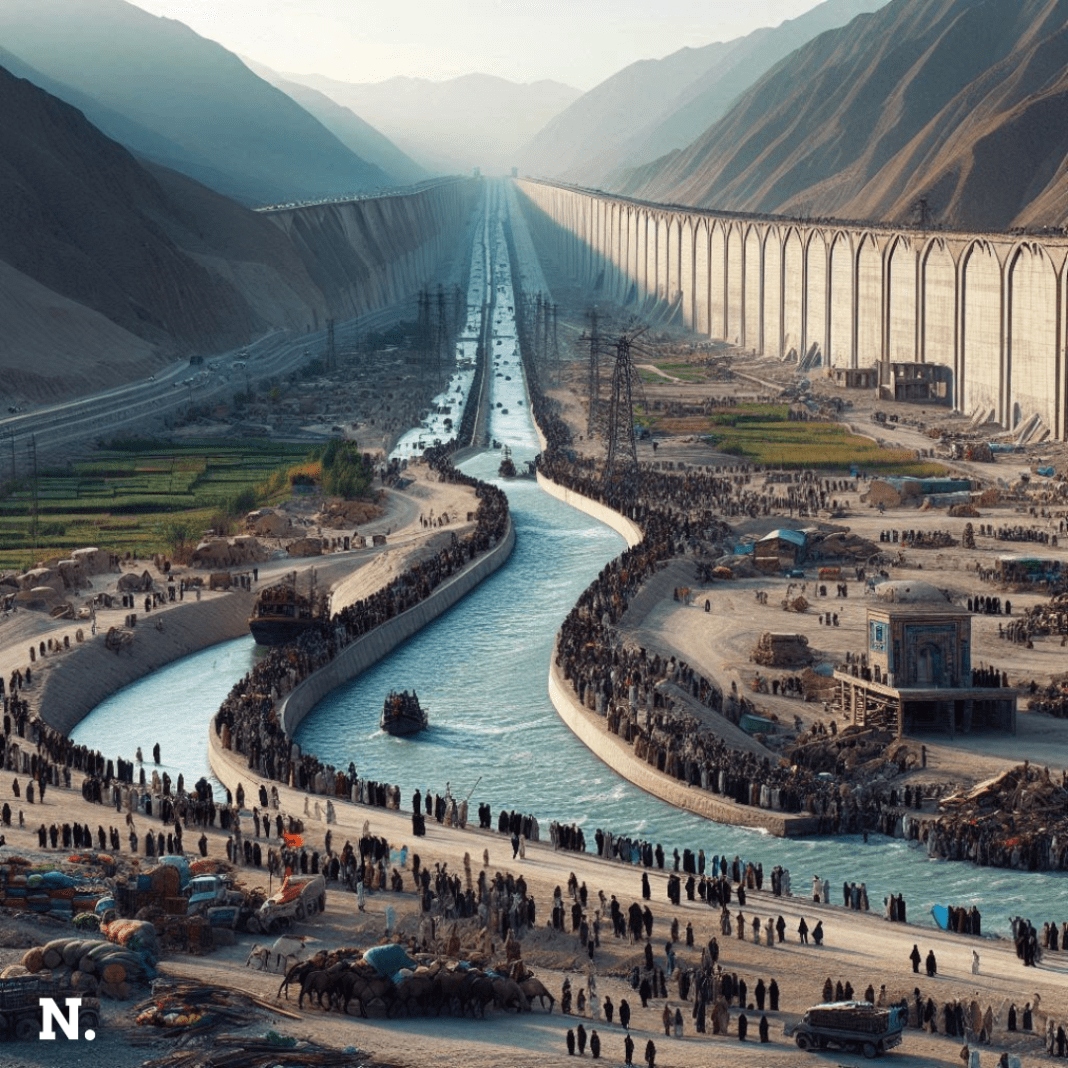

In Afghanistan the Quash Tepa Canal is under construction. It is likely to divert 20% of the water flow of the Amu Darya River which might lead to possible water shortage in Uzbekistan. Additionally it might also affect Turkmenistan’s water supply as it is further downstream.

A climate conference held in Almaty, Kazakhstan from May 27 to May 29 which included representation from Central Asian Countries. The impact of this project taken up by the Taliban Administration was discussed in a panel discussion by Rieks Bosch. He pointed out that any possible benefits would be greatly outweighed by the project’s detrimental effects on Uzbekistan.

Impact of Uzbekistan’s Agriculture

This water crisis will exponentially affect Uzbekistan’s agricultural sector. If this project gets actualised there can be significant water wastage which might increase water prices in the agricultural sector. The Taliban plans to divert one fifth of the Amu Darya’s water into the canal, a move that would necessitate a 50% reduction in water use by the Uzbek regions of Khorezm and Karakalpakstan.

One of the main concerns is water prices. Water supplied by public utilities costs between $1.20 and $1.60 per cubic meter in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, but its true value is closer to $16. This canal project will certainly spike the water prices. Water conservation efforts are underway, but there is currently no working link between resource management and pricing development.

The emphasis should now be on preserving an efficient water supply in Uzbekistan. As it already has procedures in place for both profitable and efficient water use.

History of Quash Tepa Canal

This project was ideated by the Britishers, far back in the 1950s. Later on taken up by the Russians, then Americans and now the Taliban Administration. It was officially proposed by the Afghanistan government in the year 2022. It starts from a point on the Amu Darya river in the Balkh region of northern Afghanistan.In October 2023 Afghanistan gave assurance to Uzbekistan that this project will not hamper their country’s water supply.

However, Afghanistan is resolute that this canal project can boost its agriculture industry. On the other hand Bosch has emphasized that building a canal would be easy but building an irrigation system will prove to be 10 times more difficult. Taliban might face substantial challenges to develop an efficient irrigation scheme as it has its own complexities involved.

It is estimated that without a proper irrigation system 30%-40% of the diverted water through the canal will be wasted. An artificial reservoir built near the canal is getting eroded either due to river flow or rising groundwater levels.

Role of Diplomacy and Negotiations

The Uzbekistan government is trying to establish communication with the Taliban administration, which is proving to be a difficult nut to crack. The Afghanistan administration is showing no intent of involving itself in any agreements with Central Asia on this matter.

The Eurasian Development Bank’s (EDB) chairman of the board, Nikolai Podguzov, brought attention to the dire impending water shortages in Central Asia last year. The building of the canal would make this worse.

Conclusion

Central Asia is heavily dependent on Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers for 92% of their irrigation. This region is also very vulnerable to climate change. Because of the Qosh Tepa’s subpar technology and significant water loss from leaks, it is anticipated that water flow to downstream nations like Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan would decrease.

By 2028–2029, even without the canal, it was predicted that Central Asia would experience a five–12 cubic kilometer yearly water shortfall. This will endanger its supply of food, drink, and electricity.